|

El Niño & La Niña

Misconceptions |

|

Once again El Niño is in the news and there is already lots of hand-waving and excited predictions about how it will impact this winter's weather across the United States and elsewhere. And clouding the picture even more is the hyperbole wrapped in the many myths, misconceptions and misinformation about what El Niño and La Niña are and their impacts. |

||||||

|

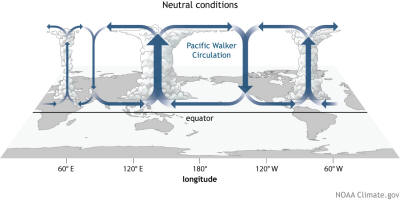

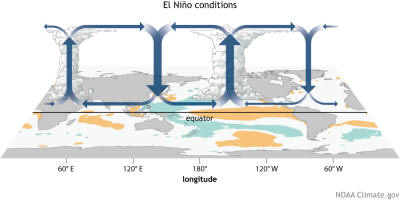

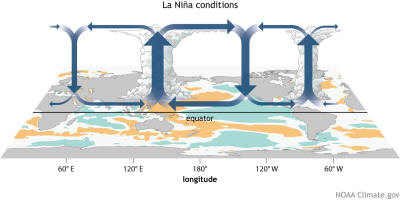

1. El Niño or La Niña will soon arrive in California No -- Neither ever comes to North America. Rather, they are phenomena that periodically occurs in the warm equatorial waters of the Pacific Ocean. Normally the trade winds along the equator push the warmest waters into the western portions of the Pacific. But on an irregular basis of typically two to five years, the trades slacken, or sometimes even reverse direction, and warmer-than-normal water accumulates along the equator in the central and eastern Pacific. This warming is called El Niño, referring to the “Christ child'' because its effects are greatest in the winter and often disrupt fishing along the South American coast around Christmastime. (The naming of El Niño) When the trades strengthen and the waters of the eastern Pacific are cooler than normal it is called La Niña.

|

||||||

|

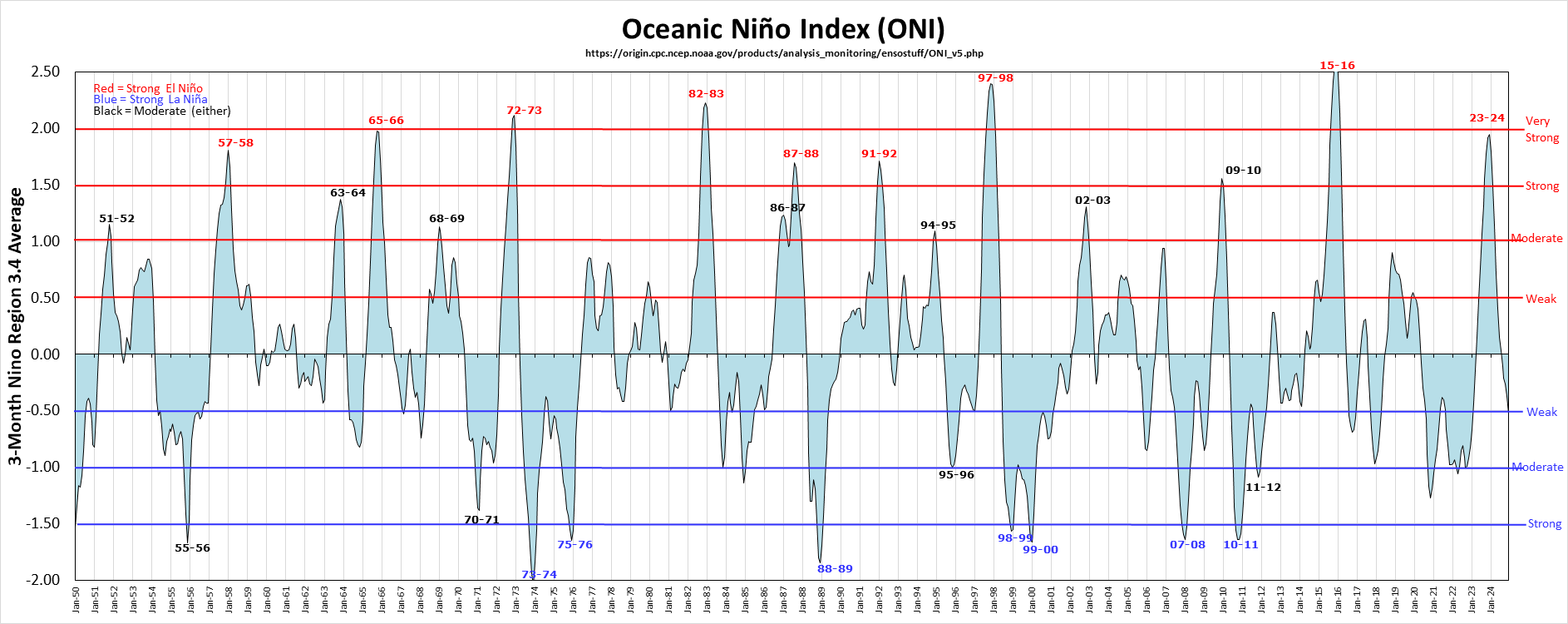

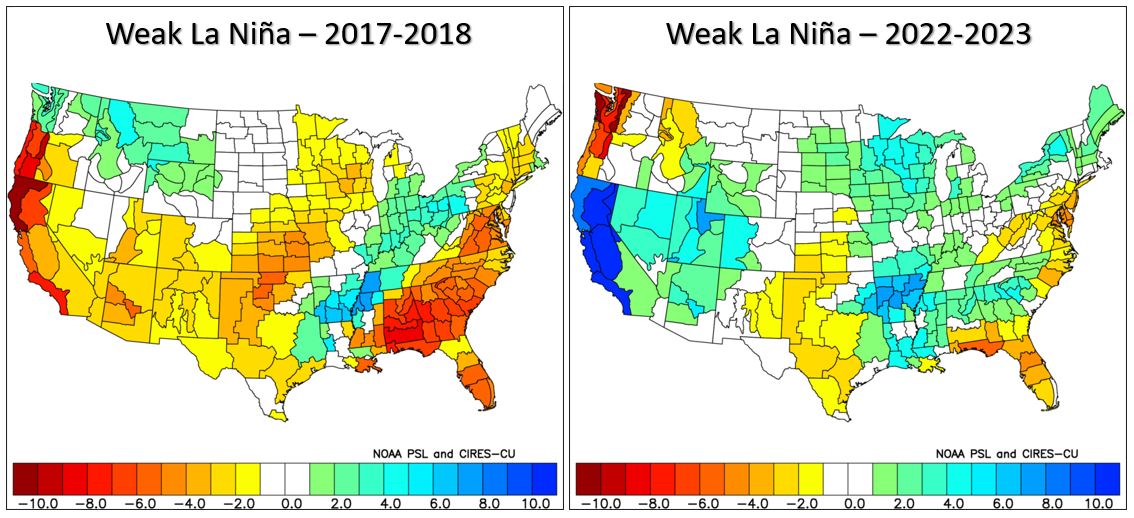

2. All El Niños and La Niñas, and their impacts, are the same No -- While El Niño and La Niña only occur in the tropics, their impacts are felt in many parts of the world. This happens because the location of the huge mass of warm water for El Niño, and cold water for La Niña, may cause the location of the jet stream, or storm track, to shift. As a consequence some regions can become warmer or colder, or wetter or drier, than historic normals. However, not all ENSO (i.e., El Niño - Southern Oscillation, the collective term for both El Niños and La Niñas) events have the same strength or location, and consequently their impacts can vary significantly. In general, the larger the area and the greater the warming of the eastern Pacific's equatorial waters, the greater the impact on other regions. The most common metric for classifying ENSO events is the Oceanic Nino Index (ONI) which identifies how much above or below normal the sea surface temperatures (SSTs) are for a specific region (i.e., Niño 3.4) of the eastern tropical Pacific. It should be noted that a number of researchers are continuing to refine the identification of ENSO events related to where within the 3.4 region and adjacent regions it occurs. Since 1950 there have been 26 years when the equatorial Pacific warmed enough to be classified as an El Niño. There have been a total of eleven seasons beginning in years (1952, 1953, 1958, 1969, 1976, 1977, 1979, 2004, 2006, 2014, 2018) classified as “weak” El Niños, seven years (1951, 1963, 1968, 1986, 19941, 2002, 2009) as “moderate”, five years (1957, 1965, 1972, 1987, 1991) as “strong” and three years (1982, 1997, 2015) as "very strong" El Niños. Conversely, there have been 25 years when the equatorial Pacific SSTs cooled than normal enough to be classified as an La Niña. A total of twelve seasons beginning in years (1954, 1964, 1971, 1974, 1983, 1984, 2000, 2005, 2008, 2016, 2017, 2022) are classified as “weak” La Niñas, six years (1955, 1970, 1995, 2011, 2020, 2021 ) as “moderate” and seven years (1973, 1975, 1988, 1998, 1999, 2007, 2010) as “strong” La Niñas. (List)  [It is extremely important to note that ENSO is not the only large scale climatological phenomena that impacts the world's weather. ENSO's impact in any given year is dependent on not only its strength but also on the location and extent of the event along the Equator in the Eastern Pacific Ocean. It's also a function of ENSO's interaction with the whole "alphabet-soup" of other Indices and Oscillations; such as the PDO (Pacific Decadel Oscillation), NAO (North Atlantic Oscillation), (AO) Arctic Oscilation (AO), (MJO) Madden-Julian Oscillation and others.] Even within the same ENSO category there can be significant differences. For example the two most recent weak El Niños, 2006-07 and 2018-19 were quite dissimilar. And the two most recent Very Strong (i.e., ONI >2.0) El Niños also had huge variations in precipitation patterns. Similarly, the most recent weak La Niñas in 2017-19 and 2022-2023 had very different winter precipitation patterns in many parts of the nation, especially California.  Extensive 1950 to 2022 ENSO US Winter Precipitation Climatologies categorized by strength can be found at US El Niño or US La Niña, and detailed ENSO Climatologies for California at California El Niño and California La Niña links. One additional takeaway is the need to look beyond more than just the ONI. A larger view is presented in Differences Between 2015-16 El Niño and Previous Strong and Very Strong Events. And not even all ENSO indices are the same as seen in Which El Niño Index is Best. |

||||||

|

3. El Niño and La Niña are storms No -- El Niño is not some sort of large superstorm that sits over an area for the winter. You will never see it on a satellite, a radar image or with your binoculars at the beach! It simply causes a pattern change that sometimes leads to variations from normal precipitation and temperature patterns. And they also do not spawn storms! El Niño and La NIña do not directly create any storms over California or anywhere else. It shifts the usual jet stream patterns so that some areas can be more susceptible to storm formation. Consequently, they should not be used as an adjective in phrases such as “El Niño flooding'', “El Niño storm” or "La Niña Drought". Think of it as the Pacific Ocean and the overlying atmosphere being on a performance-enhancing drug. And just like we don’t know why an athlete will have a great performance one day and be mediocre the next, we don’t know whether a particular weather event during an El Nino or La Niña year would have occurred anyway! |

||||||

|

4. El Niño equates to a rainy winter in California and Elsewhere No -- The real answer is not always and not everywhere. Historical records for the past seven plus decades for the San Francisco Bay Area (i.e., Hydrologic Region), show that during the twenty-six El Niño events the rainfall has been almost evenly split; with 8 of 26 years having well below normal precipitation (i.e., < 80%), 7 of 26 near normal (i.e., 80% to 120% of normal) and the final 11 of the years being substanially (i.e., >120%) above normal. See California El Niño and California La Niña. Over the same span, the Sacramento Hydrologic Region (Hydrologic Region) had eight very wet (> 120%) rainfall seasons and nine very dry (< 80%) during El Niño season. The Southern California Coast (Hydrologic Region) showed more of a wet bias during El Niño with well above normal rain in thirteen of 26 seasons, near normal for six, and well below for seven. The bottom line is that California can get wet during El Niño, but it is near or below normal almost as often. As a matter of fact, the California drought in the 1976-77 winter was during a weak El Niño. It is important to keep in mind that El Niño is not the only thing happening in the atmosphere and that other global patterns can either enhance or detract from its overall impact. |

||||||

|

In Northern California, during El Niño years, in a 2 degree square (36°

to 38° N and 122° to 124° W) between about Point Reyes and Big Sur and

about 100 miles offshore, the SSTA's were only warmer than normal in 5

of the 13 years. And during La NIña years the were warmer than normal 9

of 15 years.

The Bottom Line...

|

Copyright © 2023, Golden Gate Weather Services.

Reproduction in full or part is prohibited without permission.